Dakshineswar: A temple on the river’s edge

Rani Rashmoni’s vision is a spiritual epicentre and a symbol of universal harmony and faith

Dakshineswar Temple illuminated at night — where devotion, architecture and the quiet flow of the Hooghly come together in timeless harmony.

On the eastern bank of the Hooghly river, an offshoot of the sacred Ganga in West Bengal, stands the Dakshineswar Kali Temple with its striking nine spires and sprawling courtyard. A pulsating spiritual epicentre, it is a symbol of social defiance and the hallowed ground that nurtured one of the 19th century’s greatest luminaries, Ramakrishna Paramahansa. Its origin is a story of divine command, its history a testament to social revolution and its enduring significance a universal message of harmony.

The Matriarch’s Vision

The story of Dakshineswar begins with a wealthy, dynamic and profoundly devout widow from Kolkata — Rani Rashmoni. Born in 1793, she belonged to a lower caste by the rigid Brahminical orthodoxy of the time. After her husband, Babu Rajachandra Das, died, she took charge of his vast estate and business, proving herself to be an exceptionally astute and benevolent administrator, famously known as Rani (Queen) by the populace.

The origin of the Dakshineswar Temple is steeped in divine lore. In 1847, Rani Rashmoni was preparing for a grand pilgrimage to Kashi to offer her prayers to Lord Shiva. All arrangements were made, with a fleet of boats set to carry her, her relatives and a vast quantity of supplies. On the eve of this journey, legend tells us, the Rani dreamt of the Divine Mother, manifest as Kali, who commanded her not to travel northward to the ancient ghats of Benares but instead to raise a temple on the banks of the Ganga where the goddess would dwell for all who sought her. Profoundly moved, Rani Rashmoni immediately cancelled her pilgrimage and dedicated herself to fulfilling this divine mandate. She began a fervent search for a suitable plot of land.

Her search ended at Dakshineswar, then a serene village north of Kolkata. The 20-acre plot she found was perfect. It was situated directly on the banks of the holy river and its geography was considered highly auspicious. Part of the land was an old Muslim burial ground (gorosthan) and sacred spot for a Muslim saint, known as Gazi tala. This interfaith history, combined with the land’s shape (likened to a kurmapristha or hump of a tortoise), was deemed ideal for the worship of Shakti (the divine feminine power).

Rani Rashmoni initiated the temple’s construction in 1847, pouring her immense wealth into the project. It took eight years and an estimated Rs 900,000, a staggering sum at the time, to complete the magnificent complex.

A Revolution in Stone and Spirit

As the day of consecration neared, the temple's completion precipitated a crisis in the form of Brahminical orthodoxy. The elite Brahmins of Kolkata were outraged. How could they, the high caste, worship in a temple built by a woman of a lower caste? They declared the temple impure and decreed that no self-respecting Brahmin would serve as its priest or even accept the prasad (consecrated food) from such a source. The Rani’s social defiance had hit a wall of religious dogma.

For a time, it seemed the magnificent temple would never be consecrated. Rani Rashmoni, in desperation, consulted various pundits for a solution. The answer came from Ramkumar Chattopadhyay, a scholarly and open-minded Brahmin from the nearby village of Kamarpukur. He proposed a religious-legal solution — if the Rani gifted the temple and its lands to a Brahmin, it would technically become a Brahmin's property and thus priests could serve there without losing caste.

Rani Rashmoni accepted. She dedicated the temple in the name of her guru (spiritual guide) on 31 May 1855 on the auspicious day of Snan Yatra (the bathing festival of Lord Jagannath). Ramkumar agreed to become the first chief priest, defying the orthodox boycott. He brought with him his younger brother, Gadadhar, a young man who would soon change the spiritual destiny of the site and the world.

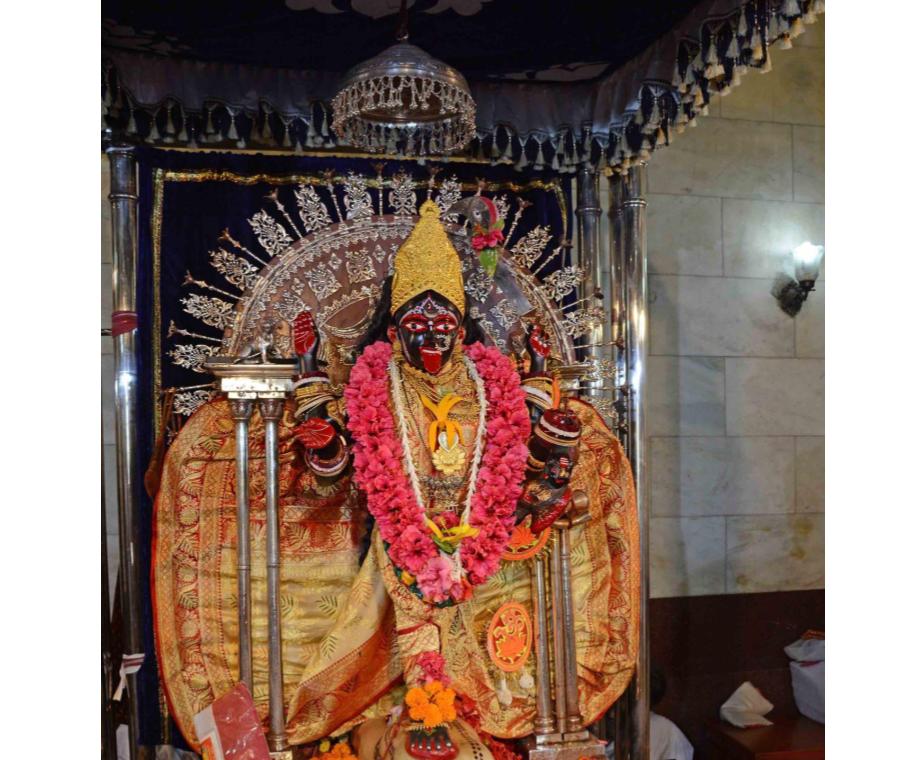

The goddess installed in the sanctum sanctorum was named Sri Sri Jagadishwari Mahakali Bhavatarini. “She who liberates Her devotees from the ocean of Samsara (the cycle of worldly existence).”

The Architecture of Devotion

The architectural form of Dakshineswar, at first glance seemingly straightforward in its vocabulary of domes, courtyards and ghats, reveals, when contemplated with the patient and lingering gaze it invites, a careful argument about the divine. The centrepiece of the temple is the grand nine-spired temple built in the nava-ratna (nine jewels) style. It is a three-storeyed, south-facing structure that stands on a high plinth with a spacious, tiled courtyard. The nine spires are clustered in two tiers with one at the top, creating an iconic silhouette against the sky. Inside the sanctum, Kali as Bhavatarini is depicted standing on the chest of a supine, white-marble Shiva. This powerful image symbolises the Advaitic (non-dual) concept that Shakti, the active, feminine, creative energy, is inseparable from Shiva, the inert, male, absolute consciousness — for without Shakti, Shiva is a shava (corpse). With her, he becomes the conscious universe.

Lining the riverfront ghat are 12 identical temples dedicated to Lord Shiva, known as the Dwadash Shiv Mandir (12 Shiva Temples). Built in the classic Bengali aat-chala (eight-roofed) style and facing east towards the sacred river, each contains a Shiva Lingam named after different aspects of the Lord. To the north-east of the main temple stands a separate, smaller temple dedicated to Radha and Krishna. This Radha-Kanta or Vishnu temple allowed for Vaishnava traditions to be practised and established the complex as a place of pluralistic worship from its very inception. At the northern end of the complex is the Nahabat, the music tower, a small, two-storeyed building where musicians would play during rituals. This gained immense significance when the tiny, austere room on the ground floor became the residence of Sarada Devi, Sri Ramakrishna's wife and a spiritual icon in her own right. To the north of the main complex, a sacred grove of five trees — Banyan, Peepal, Amla, Bael and Ashoka — was later planted by Sri Ramakrishna. This Panchavati became his open-air “laboratory” for meditation and intense spiritual practices.

The Saint of Dakshineswar

Yet, if Dakshineswar had remained only the monument of a strong-willed patroness and an exemplar of regional temple architecture, its place in history would be secure, but not outstanding. What sets it apart, what floods these spaces with an afterglow that has not dimmed, is its association with the young priest who took over worship after his brother Ramkumar's death — Gadadhar Chattopadhyay. Now, universally known as Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa.

When Ramakrishna began his service, he was not a conventional priest. He was seized by an overwhelming spiritual fervour, a divine madness (divyonmada). He eschewed rote ritual, instead developing a deeply personal, intense relationship with the image of Kali. He would talk to Her, weep before Her and plead for a direct vision. He famously described his first vision:

“The buildings with their different parts, the temple, and everything else vanished from my sight, leaving no trace whatsoever, and in their stead I saw a limitless, infinite, effulgent Ocean of Consciousness. As far as the eye could see, the shining billows were madly rushing at me from all sides with a terrific noise, to swallow me up! I was panting for breath. I was caught in the rush and collapsed, unconscious. What was happening in the outside world I did not know; but within me there was a steady flow of undiluted bliss, altogether new, and I felt the presence of the Divine Mother.”

— The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (By Swami Nikhilananda)

Dakshineswar became the crucible for his spiritual experiments. What others regarded as merely a stone idol, he experienced as the living, breathing Divine Mother of the Universe. His unconventional worship, including “feeding” the idol and experiencing long states of samadhi (ecstatic trance), bewildered the temple authorities. Mathur Biswas, Rani Rashmoni's son-in-law and the temple administrator, initially suspected Ramakrishna was mad but soon recognised his divine state.

From this base, he embarked on a journey unprecedented in religious history, practising every major path within Hinduism. He studied Tantra under Bhairavi Brahmani, a wandering female ascetic who recognised his spiritual attainments. He immersed himself in Vaishnavism, seeing Krishna manifest in himself. He pursued pure Advaita Vedanta, guided by the wandering monk Tota Puri, who helped him achieve nirvikalpa samadhi, the highest non-dual consciousness.

Ramakrishna did not stop there. Driven by an urge to “realise” the truth of other religions, he lived as a Muslim for a time, reciting the namaz and having a vision of the Prophet. He later meditated on Christ, having a vision of Jesus.

From these experiences, he forged his central, revolutionary message: “Joto Mot, Toto Poth” (“As many faiths, so many paths”). He declared that all religions are valid and true—different paths leading to the same single goal. In an era of religious exclusivism and colonial tensions, this was nothing short of radical.

The Living Legacy

The significance of Dakshineswar today transcends its architectural beauty and the remarkable story of its founding. At its very birth, the temple was a radical statement of social defiance. In an age of rigid orthodoxy, Rani Rashmoni, a non-Brahmin woman, successfully challenged the entrenched caste and gender hierarchies of 19th-century Bengal. She created a spiritual centre that, by its very existence, was open to all, setting a precedent for inclusion that would come to define its legacy.

This legacy was cemented when the temple became the cradle of the Ramakrishna Movement. The complex transformed into a magnet for the bhadralok, the intellectual elite of the Bengali Renaissance, who were drawn, often from sceptical curiosity, to Ramakrishna's simple, profound and ecstatic wisdom. It was in the sacred Panchavati grove and his small, sparse room that he trained his most famous disciple, Narendranath Dutta, who would become Swami Vivekananda. The philosophical foundations of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, a global organisation dedicated to selfless service and spiritual harmony, were laid on this very soil.

This legacy, once cemented in the teachings that emerged from the Panchavati, now draws millions to Dakshineswar as a living tirtha, a pilgrimage site of universal harmony. This immense popularity underscores its status as a historical monument and a pulsating centre of faith. The pilgrims who arrive come to worship Goddess Kali and to pay deeply personal homage, touching the hallowed ground of the Panchavati, standing in the humble room where Sri Ramakrishna lived and visiting the Nahabat where Sarada Devi lived a life of silent, selfless service.

Yet, the weight of millions of footsteps has demanded practical interventions, leading to significant recent developments like the Dakshineswar Skywalk. This elevated glass walkway, stretching nearly 400m from the railway station directly to the temple gates, was inaugurated in 2018 as a major infrastructure acknowledgment of the temple's vital importance, designed to ease congestion, ensure pilgrim safety and separate devotees from the chaotic traffic below, allowing for a more peaceful and organised approach to the sacred precincts.

But to speak only of numbers and infrastructure is to miss something essential. As Kolkata expanded and the great arterial roads and, later, the railway lines and Metro converged upon it, Dakshineswar adjusted without quite surrendering its character, though not without tension. Heritage regulations, modern crowd management and the demands of tourism now compete with the temple's unhurried spiritual routine. There is the continuous work of preserving its facades and courtyards; of guiding the throngs who come with cameras, cellophane-wrapped offerings, distracted children, fervent vows; of allowing the old rhythms of arati and mantra to continue undisturbed within an environment more hurried and more noisy than Rani Rashmoni could ever have imagined.

And yet, at certain hours, such as the pale diffusion of early morning, or the suspended hush after the evening lights, if one pauses between the river and the spires, one can feel an unbroken thread linking the nocturnal dream of a widowed zamindar, the burning quest of an obscure village priest, the arguments and reforms of 19th-century Bengal and the innumerable whispered prayers of those who come today asking for protection, for release, for some sign that the Mother has not forgotten them.